Introduction

Contemporary political dramas like House of Cards, Scandal, and Veep present public servants as bribers, cheats and cons. These shows implicitly, and sometimes explicitly, suggest that violent, vulgar, and manipulative behavior are necessary to advance in government. Political communication research often neglects consideration of prime-time entertainment in favor of news media studies. Yet considering how binge-watching is a dominant method of television consumption, I expect people expose themselves to fictional depictions of government through Netflix and other streaming services almost as often as they receive filtered mainstream media messages about actual government activity. In my research below, I conduct a content analysis of two culturally significant programs with drastically divergent tones: The West Wing and House of Cards. Specifically, I study first season episodes of both programs, and address popular takes on their ideas and impact by incorporating periodicals and books. By attentively viewing these television shows, we should recognize some common critiques of institutional behavior. While each show is critically acclaimed, commercially successful, and socially conscious, they offer divergent explanations for why government exists and how public officials interact.

Although stark attitudinal differences separate The West Wing from House of Cards, labeling their disparities as reflections of distinct creative intentions overlooks how each show approaches strategic characterization. Below I decode how showrunners Aaron Sorkin and Beau Willimon assembled their characters as emblems of common political behavior rather than concoctions of independent vision or products of pure imagination. After amassing a representative sample of scenes, I comment on factors which illustrate this division between calm and impatience, humility and ego. Though different in intention, and notwithstanding a fair dose of heroism and villainy injected to entertain audiences, Jed Bartlet, Frank Underwood, and their tight-knit inner-circles act deliberately and opportunistically, making time-sensitive judgments as whether to create compromise or conflict.

Research goals and hypotheses

Like many studying public affairs, a desire to make sense of my surroundings prompted my research of an oft-overlooked instantiation of political communication: television dramas. I would like to clarify my motivations in order to justify my methodology later on.

In light of an outsider candidate, real estate businessman Donald Trump, winning an electoral majority, many are scrutinizing whether news media outlets inadvertently helped generate an anti-establishment narrative through their coverage. I consider this reaction an affirmation of media impact, and notice a correlation to what Robert Putnam famously observed in a 1995 journal article titled “Bowling Alone.” In response to incidents like the Kennedy assassination, Watergate, and the Vietnam War, Putnam noticed a society increasingly growing detached from traditional institutions like churches and book clubs. People replaced this communal, cultural capital with television and personal technology, innovations linked to reduced civic engagement (74).

Yet more exists on television than pundits arguing over tweets. A consideration of entertainment like The West Wing and House of Cards, analyzing how fictional politics reflects and refracts interpretations of actual politics, is missing from this contemporary conversation. From a theoretical standpoint, media effects typically applied to analyze broadcast news coverage, established principles such as cultivation theory and priming, remain constructive lenses to evaluate strategic behavior on political dramas. Yet before rationalizing their specific relevance to my research, I should briefly summarize my two cases at hand and share which ways entertainment diverges from news content analyses.

Literature review

Case summaries

Broadly speaking, television succeeds as a persuasive medium by relying on a diverse visual and auditory toolkit. When effectively combined, technical instruments including cinematography, costumes, props, and sound editing produce atmosphere. Both shows to be analyzed obey a “serialized narrative” structure, meaning they feature recurring characters, and develop persistent story arcs (Butler 34). In other words, certain plots, faces and ideas flow across episodes. The West Wing follows a White House staff, led by President Josiah Bartlet, 1 year into office, suffering low job approval and depleted internal morale. Decorative set pieces, chipper orchestral music, and intimately choreographed camera movement backdrop rhythmic and detail-intense screenwriting. Brian Lowry, chief television critic of Variety magazine, called The West Wing on reflection a network program that “dared to embrace the minutiae of politics.” Meanwhile, House of Cards — based on a decade-old British series of identical title — documents the rise of Frank Underwood, a Gaffney, South Carolina representative and House majority whip determined to advance the political ladder regardless of cost. Mood lighting and regular breaking of the fourth wall help generate a sinister tone on which Willimon doubles down despite considerations to mollify.

While some subtlety exists as to precisely how Sorkin and Willimon crafted their respective universes, they both pull heavily from headlines and real public figures. This tendency persisted throughout seven seasons of The West Wing, and continues as House of Cards treks into a fifth season on Netflix. Most notably, Eli Attie, a West Wing producer and writer, contacted campaign strategist David Axelrod about drawing inspiration from a young Illinois state senator named Barack Obama, upon whom Attie ultimately designs a presidential candidate character for seasons six and seven (Freedland).

Shifting gears from production to distribution, market shake-ups are translating to what Adam Sternbergh, former New York Times Magazine culture editor, calls a “metastory” in itself. Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon, three titans in video streaming, are individually spending billions of dollars every year producing awards-quality original content. House of Cards ushered a new beginning for Netflix, validating a model only mildly explored in past by competing services. From a directorial position, Netflix offered a degree of artistic freedom unmatched by traditional networks, ABC and The West Wing included. When executive producer David Fincher met with Netflix executives, they presented him a “tantalizing” upfront guarantee of multiple 13-episode seasons (Sternbergh).

Reality construction: A strategic framework

Each program develops storylines which conform to how Dr. Murray Edelman viewed political communication. People in government build on pre-existing societal assumptions and biases to promote favorable self-narratives. A strategy often adopted by presidential administrations to perpetuate a message of strength is what political scientist Samuel Kernell called “going public,” whereby a president rallies support by directly engaging American citizens (3). High-ranking members of Congress abide by this strategy to a lesser extent. Frank Underwood arranges an alternative tactic in Chapter 1 of House of Cards: befriend a reporter. By extending insider access to Zoe Barnes, Underwood gains an outlet to spread stories damaging to president-elect Walker, retribution for breaking a cabinet appointment promise. On a systemic level, Edelman says politics undergoes a constant process of reality construction and reconstruction (1). Social problems, crises, enemies and leaders fluctuate dependent on the current cultural zeitgeist. He elaborates on this belief in Constructing the Political Spectacle, a 1988 text based in semiotics and a thorough comprehension of communication technique:

Every meaningful political object and person is an interpretation that reflects and perpetuates an ideology. Taken together, they comprise a spectacle which serves as a meaning machine: a generator of points of view and therefore of perceptions, anxieties, aspirations, and strategies. (10)

Cultivation theory

Much like Edelman, George Gerbner and Larry Gross were fundamentally interested in studying how technological mediums affect perceptions of truth. They administered a content analysis of television programming to answer whether this “central cultural arm of American society” incites or pacifies violence (175). More recent scholarship refined their research, finding that, whereas exposure to violent television news increases perceptions of crime happening nationally, people are more likely to be fearful of crime if they experienced “past victimization” or were exposed second-hand via neighbor or colleague (Gross & Aday 421). Another cultivation-esque study, an opinion survey tracing viewership tendences of 2,358 respondents, discovered that entertainment buffs tend to be less politically engaged than news junkies due to expanding media choice (Prior).

Priming

Shifting gears towards political communication, Shanto Iyengar and Donald R. Kinder introduced their priming hypothesis to postulate that television programs impact how people evaluate their elected leaders. They cemented priming in logical reasoning and other cognitive psychology pillars. “By calling attention to some matters while ignoring others,” Iyengar and Kinder theorized, “television news influences the standards by which government, presidents, policies, and candidates for public office are judged” (63). R. Lance Holbert, Owen Pillion and others extended priming from news to entertainment, The West Wing actually, in a 2003 essay, forwarding an earlier work by Iyengar, Kinder, and Peters to justify their decision. Although my methods fall short of being able to anticipate whether a more pessimistic program like House of Cards reinforces discouragement among viewers with Washington elites, priming supports saying the show prompts an audience to conjure that very question.

Methods

Extraneous scenes, those portraying nothing pertinent to policy nor strategy, were consumed yet later removed from my codebook, a Google sheet file that is accessible upon reader request. An example of a superfluous scene occurs in West Wing episode 2: Captain Morris Tulliver, a doctor caring for President Bartlet, shares a photo of his baby daughter with Chief of Staff Leo McGarry. Since this interaction bore little connection to what I am studying, expressed moments of strategic behavior, I removed it. As previously acknowledged, House of Cards incorporates frequent breaking of the fourth wall, where protagonist Frank Underwood makes off-handed remarks to spectators usually immediately following conversations with those outside his carefully assembled staff and Hill allies. Given that this habit facilitates insight into strategic decision making, these clips are included in my sample.While executing a content analysis demands an extensive time commitment, I chose to personally watch and code my cases in order to maintain internal validity. Altogether, I viewed five West Wing episodes totaling 213 minutes, and four House of Cards chapters amounting to 204 minutes. I began with pilot episodes and then consumed those episodes immediately succeeding them, chronologizing every scene in an almost ethnographic manner, observing what happens on screen and then composing a brief description. Albeit tedious, doing so allowed me to reflect honestly on character intentions. My self-defined unit of analysis is a scene, a television segment shorter than five minutes that takes place at a single location. For instances where actors transition among multiple locations during discussion, a frequent occurrence on The West Wing, I classify a scene as any subdivision containing at least one stable character existing between still moments.

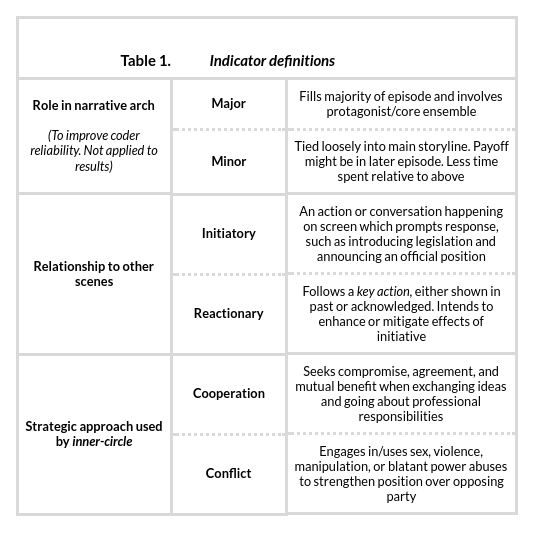

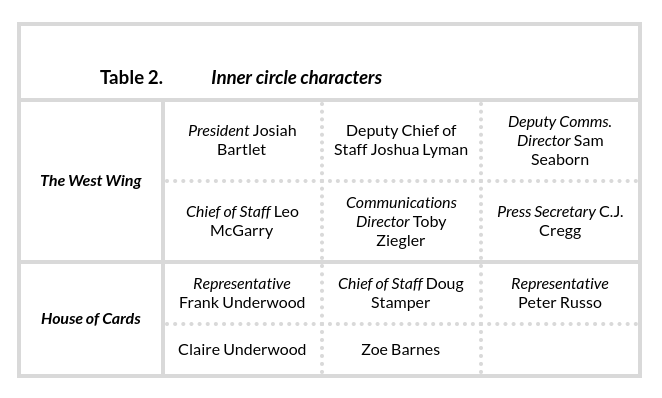

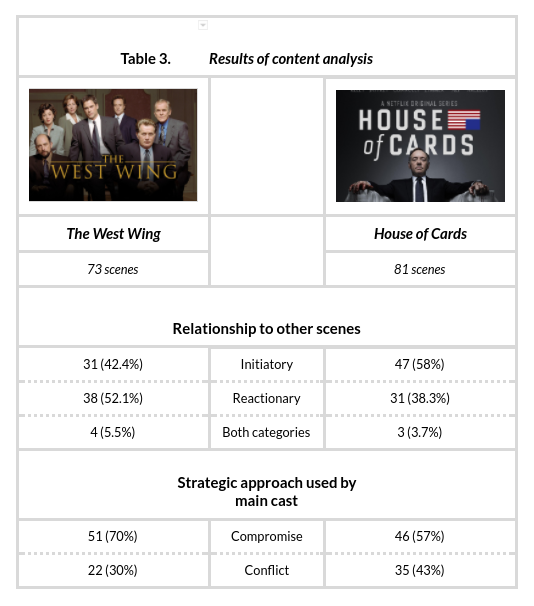

Altogether, six indicators were implemented in an examination of 154 applicable scenes — 81 from House of Cards and 73 from The West Wing. These coding categories, defined inside a table inserted two pages above, are oriented according to how core characters, main ensemble cast members, relate to a given scene. I determined who qualifies as such based on first season series credits, intending to consistently mark up my codebook based on inner-circle strategic positioning rather than according to some third party, guest star making a lone appearance. These aforementioned individuals are listed directly below.

Findings

To demonstrate my codebook with a fourth episode House of Cards scene, when Representative Frank Underwood meets Speaker Bob Birch to unify Democrats around an education reform bill, and falsely dictates that Majority Leader David Rasmussen initiated a coup against Birch to assume speakership, I checked boxes under Initiatory and Conflict, second and third-tier indicators. In that scene, Frank carries out a plan to install an ally, Congressional Black Caucus leader Terry Womack, in place of Rasmussen, while simultaneously pinning Birch by threatening to oust him otherwise.

First, sometimes more than once per episode Chief of Staff Leo McGarry gathers senior staff inside his office to preview their daily agenda. Stylistically, Sorkin only sparingly uses flashbacks. Stories proceed without visualizing these background happenings; still, everyone recognizes they exist, and develops response plans to manage long-term effects. To take an example from the pilot, we learn that 1,200 men, women and children fled Cuba on small fishing boats for Miami. In a rare moment of uniformity, Josh, Toby, C.J. and Sam all agree to send aid, food and medical supplies, rather than approach the situation militarily. Secondly, The West Wing features a press briefing room, where Press Secretary C.J. Cregg delivers official White House communication and responds to follow-up questions from news correspondents, another instance when topics other than those explicitly exhibited arise.Tabulating my data, I find that The West Wing is more reactionary in narrative arrangement than House of Cards, a program that seems to take pleasure in laying bare grotesque, upsetting, and outwardly scandalous indulgences. A small majority of West Wing scenes, 52 percent, build themselves around details never or already shown. Upon reflection, I recognize two recurring directorial motifs, based on presidential administration routines, that elucidate this discovery.

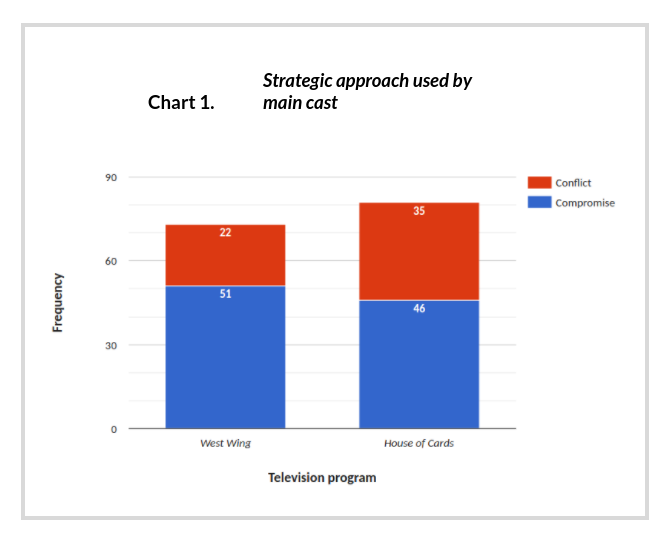

Somewhat in contrast to what I anticipated finding, House of Cards comprises itself mostly on normative strategic behavior. 57 percent of scenes gathered root themselves in cooperative approaches. As presented earlier, these are scenes where characters “seek compromise, agreement, or mutual benefit” during an exchange of ideas and whilst carrying out professional responsibilities. The West Wing split 70 to 30 percent in favor of diplomatic strategic behavior, mildly surprising for a program which critics described as “an exercise of liberal wish-fulfillment fantasy” (Lehmann). In such a utopia, collective action would presumably be perfectly successful.

The conflictory activity that materializes on The West Wing can reasonably be described as “pulling strings”. Often characters talk tough yet ultimately give into their own better angels. Morris Tulliver, the gentle-hearted White House physician mentioned before, ends up dying in an aircraft flying over Syria. Learning that rebels downed the plane carrying Morris, President Bartlet lashes out, saying “I am going to blow them off the face of the Earth with the fury of God’s own thunder.” After days of grief, and attempts to remain steadfast in advocating for a disproportionate response scenario, Bartlet commands Joint Chiefs Chairman Percy Fitzwallace to take out four “high-profile targets,” minimizing civilian casualties and potential fallout. House of Cards, meanwhile, shows outright corruption as hypothesized; a fundamentally dishonest set of characters deceitfully exude auras of goodness to gain political edge, best evidenced in Underwood planning to completely upend Democratic politics to bolster his bargaining position.Prior to voicing some final remarks, I ought to further justify this latest data point. Another coder might very well have considered modifying their scale after House of Cards, a program envisioned as pessimistic and conflict-oriented, turned out less far-gone than expected. Yet I remain loyal to my operationalization, and justify this finding thusly: in temper and intentionality, these shows greatly differ.

Conclusion

I wanted to investigate strategic behavior on television political dramas to examine whether fictional politics reinforces the historic levels of polarization appearing in actual politics. A breakdown of traditionally reliable institutions underpins a divided media environment, where consumers watch news networks that match their partisans views, promoting an echo-chamber effect deconstructive for mending societal wounds (Prior). To study this landscape, I devised a content analysis of two television programs — The West Wing and House of Cards. Despite depicting protagonists at divergent points in their careers, showrunners Aaron Sorkin and Beau Willimon forward a similar set of political norms. Where these shows sunder is their belief in upholding these strategic rules which value honest conversation over conflict. Frank Underwood would call them mere guidelines, and project a systemic frame viewing public servants as egomaniacs and Washington as a ruthless operating environment. Although my methods are only sound enough to establish a correlation between strategic approaches on televised entertainment and political attitudes, future work should continue studying narrative intentions, contrasting compromise and conflict-oriented behavior, and expand political communication research to encompass other forms of media.